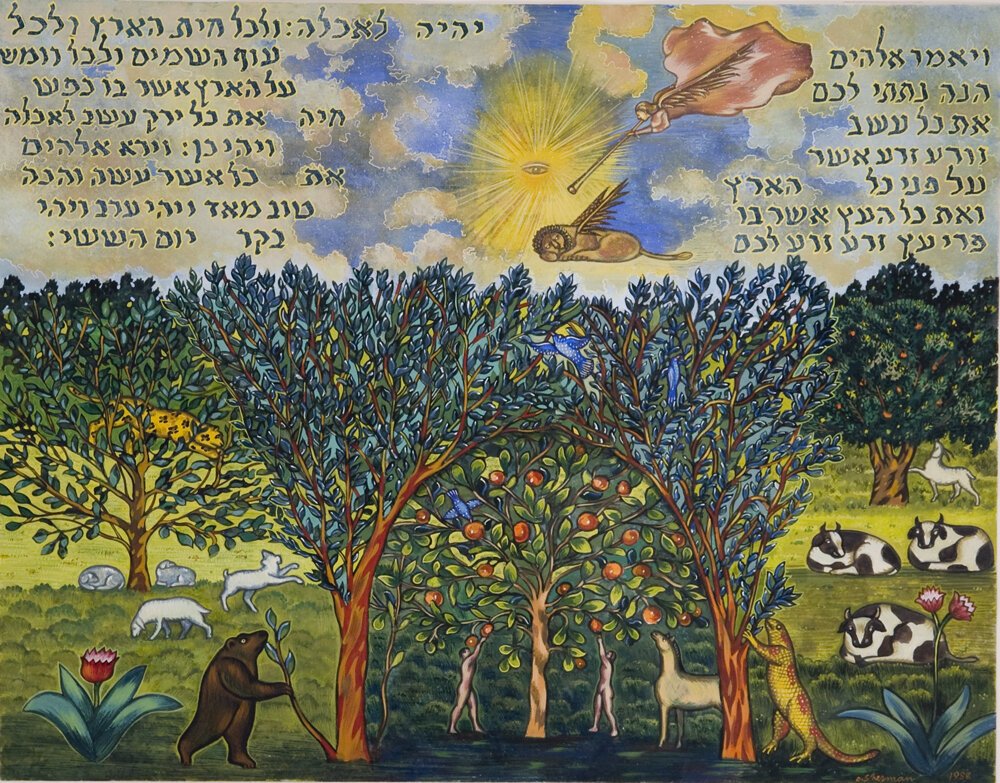

A MEDITATION ON TU BISHEVAT

The calendar of Israel, as established by the Rabbis of the Talmud, has four distinct “new year” celebrations:

The civil new year falls on Tishri 1.

The Biblical new year is observed on Nisan 1.

The new year from which Temple tithes are calculated is on Elul 1.

The new year for trees is on Shevat 15, or Tu BiShevat.[1]

Though Tu BiShevat is not a festival mandated by the Torah, it finds its origins in this law in Leviticus 19:23-25: “When you come into the land [of Israel] and plant any kind of tree for food, then you shall regard its fruit as forbidden.[2] Three years it shall be forbidden to you; it must not be eaten. And in the fourth year, all its fruit shall be holy, an offering of praise to the LORD. But in the fifth year, you may eat of its fruit, to increase its yield for you: I am the LORD your God.” Leaving a tree unpruned and unharvested for the first three years is good horticultural practice. The fourth year’s fruit was given to the Temple as a praise offering for the land’s abundance. From the fifth year onward, the fruits of the tree were for the farmer.

This tithing law raised the question of how to calculate the ages of the trees. Rather than tracking the individual dates of planting, the Jewish sages ruled that Tu BiShevat would serve as a “birthday” for all trees, and tithes could be determined using that date. The day and season were suitable to mark this beginning; winter rains had fallen and soaked the ground by this time, and conditions were ripe for new growth. Almond trees had begun to blossom white and pink, and signs of hopeful spring had started to emerge.

However, with the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century A.D. and exile of many Jews out of Israel’s land, Temple tithe calculations became a pointless exercise, and Tu BiShevat faded from the calendar. Tu BiShevat experienced a revival in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, however, when Kabbalistic communities transformed the utilitarian date into a celebration of the mystical connection of creation and Creator. In more contemporary times, as the Jewish diaspora has returned to the land of Israel in larger numbers, the observance of Tu BiShevat has shifted back to a practical expression of ecological stewardship. “Redeeming the land,”[3] tree-planting programs, and celebrations featuring locally grown fruits all occur on this “Jewish Arbor Day.”

Of all Tu BiShevat’s various iterations—tax date, mystical celebration, or ecological holiday—it is perhaps this latest rendition that aligns most with the motif of fruit trees in creation that bookend and permeate the Biblical narrative and the honors the eternal vocation of man as a gardener-king.

Two Trees and the Promised Seed

Indeed, the Bible begins in an abundant garden in the region of Eden filled with fruit trees: “And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there He put the man whom He had formed. And out of the ground the LORD God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for good. The Tree of Life was in the midst of the garden, and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. … The LORD God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it. And the LORD God commanded the man, saying, ‘You may surely eat of every tree of the garden, but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.’”[4]

God’s discipleship of humanity, His raising them as fit and wise stewards of His creation, was facilitated by two fruit trees. Would humans choose the way of life, be formed by obedience, and taught what is good by Goodness Himself, or would they prefer a shortcut to knowledge not imparted by God, leading to their death?

Another created being would be the catalyst for mankind’s fall from grace: a serpent. This ancient snake deceived our mother Eve into choosing to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and she, in turn, gave this forbidden fruit to her husband Adam, and he disobediently ate it as well.

When the LORD God came to judge these acts of disobedience, He first pronounced the following to the serpent: “Because you have done this, cursed are you about all livestock and above all beast of the field; on your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; He shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise His heel.”[5]

God then turned to Eve, saying, “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Your desire shall be contrary to your husband, but he shall rule over you.”[6]

To Adam, the LORD God said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for our to it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”[7]

The justice in these pronouncements of God is beautifully and terribly apparent. He had charged the man and his wife to “be fruitful and multiply,” “fill the earth and subdue it,” and to “work and keep” His garden in Eden. They still have this general mandate, but the accomplishing of it will now be painful and toilsome. The bearing of humans will be painful. The cultivation of the land will be painful. And the days filled with pain and toil will ultimately end with a return to the soil. To protect Adam and Eve from eating from the Tree of Life and living forever, unendurably prolonging their sin-stained existence for eternity, God mercifully cast them out of the garden and set a guard of cherubim and a flaming sword over the Tree of Life.

Like so many of the judgments of the Lord that would follow, there is a promise of hope amid consequences for sin. The seed of the woman would have His revenge on the deceptive serpent. Perhaps this seed would be the catalyst reversing the toil and pain of life, maybe even making a way to return to the garden and eat from the Tree of Life.

Almonds and Resurrection Assurances

Generations came and went, and every new birth carried with it a question: "Will this one be the promised seed?" But though some men called upon the name of the Lord, brought relief, had divine covenants made with them, and received more detailed words on man's hope to escape judgment to a renewed creation, wickedness increased on the earth, and nature bore the scars of its fallen state.[8] Families split, and nations warred with each other. Man oppressed man, and as he increased and multiplied, he built systems that perpetuated injustice on greater and greater scales.

Amid this ever-growing evil, God called a specific family from the line of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to be the bearers of the promised seed, and because of this, they were people set apart. Famine drove them to a land called Egypt. Though they initially brought relief to their host nation and their host nation saved them from starvation, it wasn't many generations before this minority became enslaved and subjected to bitter labor. The Hebrews' cries reached the heavens, and after 430 years, the Lord brought them out of Egypt with mighty judgments on their oppressors. But though the Hebrews were a people who had suffered much, they were far from perfect and often rebelled against the authority of the Lord, disobeying the God who had saved and sustained them through many hardships. As they marched through the wilderness between Egypt's slavery and the fulfilment of possessing their promised land, a pattern emerged. The Hebrews would grumble. They were fed up with the hardships of wilderness living and were nostalgic for the material comforts they left behind in Egypt. They would chafe under Moses' leadership and would be frustrated by the general state of affairs. This complaining and subsequent acts of rebellion would incite the wrath of God, causing Moses to intercede on behalf of the "stiff-necked people," and God would relent from His judgment.[9]

Numbers 16 and 17 record one such occurrence of this pattern when two rebellions combined into one. On the one hand, a Levite named Korah, challenged Moses and Aaron, his brother, over leadership in the priesthood. On the other hand, two men of the tribe of Reuben, Abiram and On, complain that Moses has not fulfilled his promise of land, but is using the wilderness wanderings as a means of political control. The Lord, who knows the hearts of men, dealt with both the spiritual and political rebellion swiftly. Korah and his followers are consumed by fire in front of the Tent of Meeting as they tried to offer incense to the LORD. Abiram, On, their followers and Korah's family, are swallowed alive by the earth from their tents' entrances. The people were terrified in the face of such swift and terrible judgment, but instead of turning to the LORD and rejecting the fruit of their rebellion, they quickly began to accuse Moses and Aaron. God was understandably furious, and as He had threatened many times before, told Moses that He would put an end to the people. A plague began to break out and kill the Hebrew people, and Moses instructs Aaron to quickly go and make atonement, standing in-between the dead and the living. When Aaron does so, the plague is held back, but not before 14,700 people die in addition to those already consumed by fire and swallowed by the earth.

In a generous concession to a people who would not relent from their doubts no matter how much carnage followed their lack of faith, the LORD suggested to Moses a final sign to confirm Aaron's election and the house of Levi to the priesthood. "Speak to the people of Israel, and get from them staffs, one for each fathers' house, from all their chiefs according to their fathers' houses, twelve staffs. Write each man's name on his staff and write Aaron's name on Levi's staff. For there shall be one staff for the head of each fathers' house. Then you shall deposit them in the tent of meeting before the testimony, where I meet with you. And the staff of the man whom I choose shall sprout. Thus I will make to cease from me the grumblings of the people of Israel, which they grumble against you."[10]

So Moses collected twelve staffs[11] with the twelve leaders names written on them and placed them before the LORD in the Tent of Meeting. The next morning, Moses found that Aaron's staff had bloomed, flowered, and born almonds. He brought them before the Israelites, and the LORD said to Moses, "Bring back Aaron's staff before the Ark of the Covenant as a safekeeping, as a sign for rebels, and let there be an end to their murmuring against Me, and they shall not die."

Like the rainbow after the flood, so was the sign of Aaron's flowering staff after the judgment of the rebellion of Korah. God gave a sign that He had in fact elected Aaron as a priest by this small resurrection and miraculous fruitfulness, doubly miraculous as the Levites themselves were forbidden from farming by their priestly duties. God would not be mocked: Sheol swallowed the wicked whole, fire consumed the unrighteous, and pestilence struck down both young and old—sparing none, for none were innocent. But the same God who had continued the promised seed line through barren womb after barren womb of the matriarchs was again showing that He could bring life from the dead—fruit from deadwood—and offering hope amid judgment.

Figs and Judgment Pronouncements

Many more crises of faith and promises of deliverance would mark the history of the Israelites. They would come into their promised land, but as the law that Moses brought down from Sinai for them decreed, should they neglect to uphold the law, there would be a curse on them as a people. Not only would the land fail to yield its fruit,[12] but it would also ultimately expel them and doom them to exile.[13]

Israel existed first under the rulership of judges and then of kings. God Himself assured one king particularly, David, that his dynasty would birth the promised seed, who would rule from David’s throne forever. For over seven hundred years, the twelve tribes lived in the land of Israel. Then, in approximately 720 B.C., the Assyrians crushed Israel’s northern kingdom and subjected the ten northern tribes to exile. A hundred and twenty or so years later, the Babylonians conquered the southern kingdom, destroying the First Temple, and subjecting the southern two tribes to exile.

But just as the LORD heard the groaning of His people in Egypt, so now He heard the sighs of His children in Babylon. After seventy years of exile, Cyrus of Persia, allowed Jews to return to the land, and the Second Temple’s construction took place. But less than two hundred years later, Alexander the Great would conquer the land, and it would be pass to the Ptolemies and then to the Seleucid empire under Antiochus III. Antiochus desecrated the Second Temple and was subsequently overthrown by the Jewish Hasmoneans (Maccabees) in 129 B.C. Again Jewish autonomy would be short-lived, as they were conquered in 63 B.C. by the Roman general Pompey.

During this time of Roman occupation, a young rabbi named Yeshua (Jesus) began His ministry. Rumors swarmed around Him, indeed around many leaders of rebellions at the time, that this was indeed the Messiah. Could he be the promised seed, the son of Abraham, the son of David, destined to free Israel from her oppressors, judge the nations, rule the earth from Jerusalem, and break the never-ending cycles of sin, rebellion, exile, and death—returning the fallen creation to the glorious and unblemished beauty of Eden. Many Jews assumed that this overthrow of sin and death would be brought about only by military conquest, as the prophets had foretold. They were likewise ready to overthrow the Romans and bring about this eternal Messianic kingdom in their own strength.

Such was Jerusalem’s atmosphere in the early springtime as Jesus and His disciples traveled from Bethany to Jerusalem. Jesus had just previously entered Jerusalem on a donkey to crowds throwing down their cloaks and proclaiming His Messiahship by saying, “Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our father, David! Hosanna in the highest!”[14] Now, as He approached the city, He felt hungry and saw a fig tree. But when He got closer to the tree, He saw that there was no fruit. Indeed, it was not surprising, as it was not the season for figs. Despite this fact, Jesus said to the tree, “May no one ever eat fruit from you again,” in His disciples’ hearing. They all continued to Jerusalem.

When they reached the Temple, Jesus began to drive out those who bought and sold in the Temple, overturning tables and knocking over chairs. Quoting the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah, He called out, “Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations’? But you have made it a den of robbers.” He said this in the chief priests’ and scribes’ hearing. Jesus and His disciples then left Jerusalem.

On the road, they passed the fig tree that Jesus had spoken to on the way and were astonished to see that it had withered to its roots. “Rabbi, look!” they exclaimed. “The fig tree that you cursed has withered.” After the righteous anger of the Temple’s cleansing and the triumphal entry of Jesus in Jerusalem, here seemed to be another demonstration of raw, dominating power. Jesus, as per usual, had a surprising reply: “Have faith in God. Truly, I say to you, whoever says to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and thrown into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart, but believes that what he says will come to pass, it will be done for him. Therefore I tell you, whatever you ask in prayer, believe that you have received it, and it will be yours. And whenever you stand praying, forgive, if you have anything against anyone, so that your Father also who is in heaven may forgive you your trespasses.”[15]

Jesus had just had two very different experiences in Jerusalem. The first appeared to be positive—Jesus received a kingly welcome that seemed to fulfill messianic apocalyptic prophecy.[16] However, the second visit caused righteous anger to flare in the face of the extortion taking place in Gentiles’ court. Israel was meant to be a light to the nations and her Temple a place of prayer, but instead, the scribes and chief priests had requisitioned the area where the nations could pray to line their own pockets.

Though Jerusalem had initially seemed like she might be ready to receive her king, though her leaves were green, she bore no fruit. A distressed Jesus, who knew what she would have to go through before she would again say, “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the LORD,” wept. Despite hopes to the contrary, it was not the season for figs. (The prophets often used the fig tree to symbolize Israel,[17] and the destruction of the fig tree had been used to illustrate judgment.)[18] Jesus cursed the tree that bore no fruit His disciples’ hearing for the same reason He rebuked the scribes and the chief priests in their hearing. Those in the Temple had failed to steward their mandate, and their downfall shows the consequences of faithlessness and fruitlessness. In light of this sign of destruction, Jesus encouraged His disciples to keep the faith. To pray with expectation. To forgive without exception. For though Jerusalem’s road to redemption would be rocky indeed, it would not be too difficult to redeem for the God who brought forth Isaac in Sarah’s and Abraham’s old age or made Aaron’s staff of dry, dead wood flower and bear fruit. The season of figs would come.[19]

Cursed is Anyone Who Hangs from a Tree

While the only recorded destructive miracle of Jesus involved the death of a fig tree, His own death occurred just a few days later by “hanging on a tree”—a type of execution that bore a curse. The Law states that “If a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is cursed by God.”[20] It was brutal punishment—the kind of death that polluted even the land. Such a sentence could not possibly fall on God’s anointed, the Messiah of Israel, reasoned the crowds who gathered to watch Jesus’ crucifixion. As Jesus was lifted up, nailed to the wooden crossbeams of that dead tree, passers-by mocked him, saying, “He is the King of Israel. Let Him come down now from the cross!”[21] They did not understand the prophetic words that Jesus, the promised seed of Genesis 3, had uttered less than a week before, “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified. Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.”[22] Peter later explains that the cursed death was necessary, since Jesus “bore our sins in His body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness.”[23] Death and resurrection turned the curse of sin against itself, and Jesus would rise vindicated as the first-fruit evidence of our future resurrection. The power of sin which banished man from the Tree of Life and sentenced him to futility in performing his call as gardener-king would be broken for all who believed on the name of the promised seed—Jesus.

Paul, the rabbi from Tarsus, highlighted the broad scope of such a brilliant maneuver when he explained it to the Galatian church this way: “Messiah redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree’— so that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles so that we might receive the promised Spirit through faith.”[24] Not only would the Messiah of Israel set in motion the eventual shattering of the cycle of sin, rebellion, fruitlessness, death, and exile that the curse of the Law mandated for Israel’s national lawbreaking, but also begin an acceleration of the covenant promise to Abraham, that the election and calling of His family would bless the families of the earth.[25]

Olives and Life from the Dead

The Gentile inclusion that Paul briefly touched on in his letter to the Galatians, he expanded on in another letter to the church in Rome. The promised seed and His saving work was not only for His people Israel, but for the nations that pledged their allegiance to the Jewish Messiah. From the time of the Exodus, a “mixed multitude”[26] had accompanied the chosen people, declaring as Ruth would to Naomi in her own journey: “Your God will be [our] God.” This minority of foreigners living in the land[27] notwithstanding, the hope of Israel was by and large unknown to the Gentiles. Though many in Israel received the message of the Messiah when He came, the vast majority of Jews “did not know the time of their visitation”[28] and in a matter a few centuries, far more non-Jews would worship the Jewish Messiah than Jews. This presented a theological problem: how could the Messiah return as a King of a people who had largely rejected Him? Was Israel eternally doomed as the cursed fig tree withered to its roots? Had the blessing promised through Israel missed Israel altogether?

Paul’s answer is emphatic: “By no means!”[29] “For now,” he continues, “there is a remnant preserved by grace.” He compares the nation of Israel to a cultivated olive tree. Just as fruitless branches are broken off the tree, so were those in Israel who persisted in unbelief. He then compared Gentile partakers of the promises to “wild olive shoots” grafted in among the cultivated branches and nourished by the same, unchanged roots of that cultivated olive tree. “Branches have been broken off that you might be grafted in,” writes Paul to the Romans, “But if Israel’s temporary rejection of their Messiah means that Gentiles will have an opportunity to accept the promises of God, what will happen when Israel finally receives her King? The resurrection—life from the dead.”[30]

The Leaves of the Tree were for the Healing of the Nations

The day when all Israel will be saved, and the righteous rise incorruptible, and the Messiah rules from Zion will only be the beginning of the renewal of all things. The olive tree company—natural branches and wild, grafted-in shoots—under the just leadership of Jesus and free from the judgements of sin and death, will fully and finally do what they had been called to do from the beginning. They will tend the land: healing and cultivating it to greater and greater degrees of glory. “Every man shall sit under his vine and fig tree, and none shall make him afraid.”[31]

After a thousand years, the New Jerusalem will descend from heaven, and her geography echos and exceeds the descriptions of that original garden in Eden: “Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city; also, on either side of the river, the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, yielding its fruit each month. The leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.” [32]

“As it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be.”[33] No longer barred from the tree of life, the redeemed world will partake of its fruit for endless ages—healed, whole, and glorious.

Amen. Maranatha.

Devon Phillips is just a pilgrim longing for the Day of the revealing of the sons of God and the redemption of our bodies. Meanwhile, she is privileged to serve in the Middle East with Frontier Alliance International and contributes regularly to THE WIRE. She can be reached at devon@faimission.org.

[1] These two customs, are called “Mishloach Manot” and “Matanot la'evyonim.” Mishloach Manot is the practice of giving gifts to friends and family and Matanot la'evyonim is the act of giving gifts to the poor. Rabbi David Fohrman explains the origin of these customs in this video: https://www.alephbeta.org/playlist/mishloach-manot-matanot-laevyonim

[2] Particularly in contemporary western Christianity, the genealogies of Scripture are often treated as yawn-inducing and irrelevant information, a carry-over from ancient eastern cultures when family lineage had more meaning. But one of the major themes of the Scripture is tracing the promised seed of Genesis 3 to its fulfillment in Jesus. When covenant and prophesy are so centered on family and descendants, genealogies should be primary tools in following this major storyline.

[3] Exodus 17:8–16; Deuteronomy 25:17–19

[4] Exodus 17:14–16

[5] Numbers 24:17–20

[6] 1 Samuel 15:3

[7] 1 Samuel 15:9

[8] 1 Samuel 15:22-23

[9] The Amalekites were decedents of Esau and the Benjamites descendants of Jacob. It is interesting to note that Benjamin was the only one of Jacob’s 12 sons who did not bow to Esau, having not yet been born.

[10] Not only did Mordecai righteously adopt and raise his orphaned cousin Esther, but he earnestly cared for her, as evidenced by his daily checks on her welfare in the king’s harem. See Esther 2:11.

[11] Esther 4:13-14

[12] The word often translated as “gallows” in Esther’s English translations is the Hebrew word _ets_ which literally means, “tree.” The common means of execution in Persia at the time was impaling on a stake, and then being “hung” or displayed on a wooden pole. The cross is similarly described as a tree.

[13] Zechariah 2:8

[14] 1 Corinthians 2:7-8

[15] Acts 1:6

[16] Revelation 11:15

[17] Acts 1:8

[18] This persecution ironically and tragically was often at the hand of the “followers” of those apostles who yearned to restore Israel under the leadership of her Messiah.

[19] In 2015, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said there would be "nothing" left of Israel by the year 2040, which prompted clocks counting down to that date. See: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/iran-al-quds-day-protest-clock-president-hassan-rouhani-a7806056.html

[20] https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2020/september/iran-christian-conversions-gamaan-religion-survey.html

[21] See documentaries Sheep Among Wolves and Sheep Among Wolves: Volume II for first hand accounts from Iranian followers of Jesus.

[22] Jeremiah 49:35–39